A scheme that federal authorities have called the “largest pandemic fraud in the United States” reached inside Minneapolis City Hall when three recently departed mayoral appointees were indicted on fraud charges.

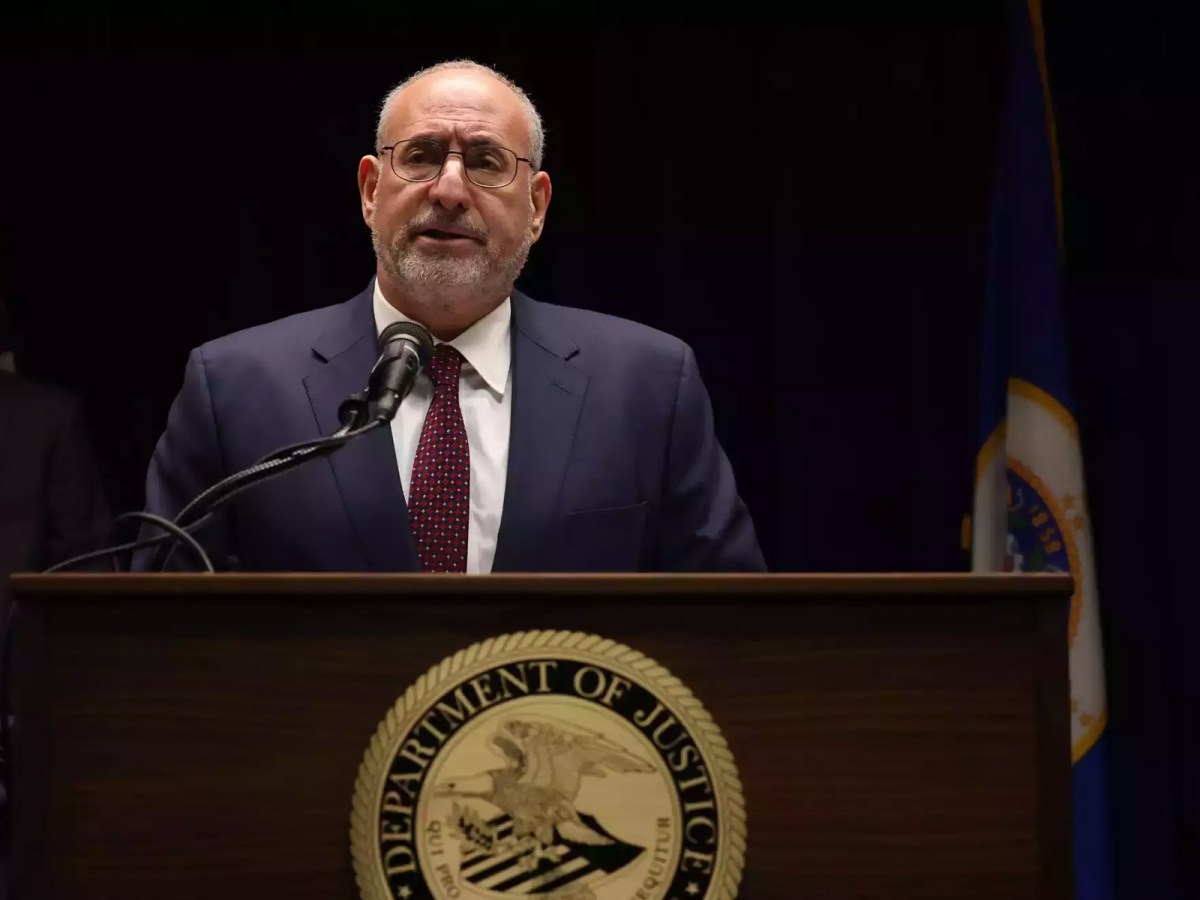

Mayor Jacob Frey’s former senior policy aide and his previous appointee as board chair of the public housing authority both face charges of defrauding the federal government in a scheme to spend millions of dollars in food-aid funds for personal use. Another Frey appointee—a former member of the mayor’s community safety workgroup—also faces charges in the case. The three men are among 48 people charged so far in the food-fraud case, as detailed in sweeping indictments that Andrew Luger, the U.S. Attorney for Minnesota, unveiled Tuesday.

All three—Abdi Salah, Sharmarke Issa, and Abdikadir Mohamud—left their posts by the end of February after they were implicated in court documents connected with the case.

The indictment says that for the purposes of carrying out the food-fraud scheme, Abdi Salah acquired the nonprofit Stigma-Free International in October 2020 from someone identified in indictments only as “Individual A.”

Jamal Osman, a Minneapolis City Council member, told Sahan Journal in January that he founded Stigma-Free International but stepped away in the summer of 2020 because of his run for office.

Jamal has not been indicted or accused of wrongdoing. He did not respond to an interview request or written questions from Sahan Journal this week.

A Frey spokesperson said the mayor was not available for an interview and sent a brief statement: “We are grateful to U.S. Attorney Luger for his work on this case. The allegations are appalling.”

According to the indictments: During the COVID-19 pandemic, nonprofits and businesses that were supposed to feed low-income children instead fabricated and reported 125 million nonexistent meals, billed the United States Department of Agriculture, and pocketed as much as $250 million. Prosecutors allege that people running the food sites went so far as to invent names and ages for the nonexistent children they were supposedly feeding.

The indictments allege that a “sponsor organization” called Feeding Our Future served as an intermediary, distributing the federal funds to nonprofits and businesses that claimed to provide the meals.

Three of the people allegedly part of the scheme also had roles at Minneapolis City Hall.

Abdi Salah, 34, a senior policy aide to the mayor, was fired from his position in February, hours after Sahan Journal asked the mayor’s office about a federal court document that listed his name in connection with the food fraud. Federal authorities alleged that he had used money that should have gone to feeding children to purchase a $390,000 multi-family home with a business partner, Sharmarke Issa.

Sharmarke, 40, was then the board chair of the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He resigned from his position in February when the property he owned with Abdi appeared on federal court documents seeking forfeiture of properties allegedly purchased with stolen money.

Abdikadir Mohamud, 30, was appointed to the mayor’s community safety workgroup in December 2021. After Abdikadir’s name appeared in public search warrants in the food-fraud case in January, and Sahan Journal asked the mayor about it, Frey said he was no longer part of the workgroup.

Luger announced charges against all three—Abdi, Sharmarke, and Abdikadir—–on Tuesday, including wire fraud, conspiracy to commit money laundering, and money laundering.

Sharmarke did not respond to a Sahan Journal’s request for comment via text message. Abdi Salah’s lawyer, Brian Toder, declined to comment. Abdikadir’s lawyer, Kyle White, said Friday he would consult with his client about Sahan Journal’s request for comment.

Abdi pleaded not guilty; Sharmarke and Abdikadir have not yet entered pleas.

The reinvention of Stigma-Free International

The scheme, detailed in extensive federal indictments, involves dozens of shell companies that allegedly committed fraud.

But for two of the indicted mayoral appointees, one nonprofit proved central: Stigma-Free International.

According to documents filed with the Minnesota Secretary of State, Jamal Osman incorporated Stigma-Free International as a nonprofit in August 2019. He told Sahan Journal in January that before joining the City Council, he delivered crisis mental-health training to businesses under the banner of Stigma-Free International.

In August 2020, Jamal won a special election for a seat representing parts of south Minneapolis, including the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood. He previously told Sahan Journal that he stepped away from Stigma-Free International in June 2020 because of his run for office.

Public documents at the Secretary of State’s Office show that in October 2020, the nonprofit made the relatively unusual move of filing new paperwork to list a new set of people as “incorporators.” Jamal’s name is no longer listed on official Secretary of State documents after October 2020. Another individual, Ahmed Artan, became the nonprofit’s new registered agent.

The indictments unveiled Tuesday reveal that someone else was involved in that transaction: Jamal’s colleague at City Hall, Abdi Salah.

From mental-health advocacy to food-fraud nexus

In October 2020, the Minnesota Department of Education announced that the United States Department of Agriculture would no longer allow restaurants or other for-profit companies to serve as food sites–that is, the places physically serving meals or distributing food. Restaurants could serve as vendors—providing food for other nonprofit sites—but they could not serve as distribution sites.

Any distribution sites at restaurants would have to close at the end of October, the education department announced.

The FEEDING OUR FUTURE INVESTIGATION

That’s when owners and associates of Safari Restaurant—including Abdi Salah, whose brother owned the restaurant—acquired the nonprofit Stigma-Free International to carry out the fraud scheme, authorities say. As a nonprofit, it was not subject to the restrictions on restaurants or other for-profit companies.

According to the indictment, “Individual A” had incorporated Stigma-Free International as a nonprofit in August 2019. (In court documents, authorities generally omit names for people who are not charged.) Secretary of State incorporation documents show that Jamal Osman, along with three others, registered the nonprofit in August 2019. Jamal signed the registration paperwork submitted to the Secretary of State.

The indictment states that in October 2020, “Individual A” provided Stigma-Free International’s board minutes and incorporation documents to Abdi Salah.

Abdi then forwarded those to Ahmed Artan. Abdi sent “Individual A” new board minutes announcing the resignation of “Individual A” as president and the appointment of Ahmed as president.

After amending these documents, “Individual A” was no longer in charge of the nonprofit—Ahmed was. (Ahmed did not respond to an email request for comment, and his lawyer did not return a voice message. He pleaded not guilty in federal court Tuesday afternoon.)

The indictments do not explain why “Individual A” may have agreed to transfer the nonprofit to Abdi.

On October 9, two days after Ahmed became president, he and Feeding Our Future Executive Director Aimee Bock prepared applications to operate federal food programs through Stigma-Free International. By October 20, Stigma-Free Willmar claimed to be serving meals to 3,000 children per day, seven days a week. (Bock has pleaded not guilty and maintained she is innocent.)

In a matter of days, Stigma-Free International had transformed itself from a seemingly dormant mental-health training organization into a venue where thousands of children could supposedly receive free meals. But according to federal authorities, Stigma-Free served very few meals. A clear example, which U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger described in his press conference announcing the charges, came from Stigma-Free Willmar.

Abdikadir Mohamud, whom the mayor later appointed to his community safety workgroup, ran the Stigma-Free Willmar site, along with Ahmed Artan. In a city of 21,000 people, Abdikadir submitted a meal roster with names of 2,000 children—a list that would have amounted to half the students in the Willmar Public School District. But only 33 names on the meal roster matched the names of children enrolled in the school district, Luger said.

All told, Abdikadir Mohamud allegedly embezzled more than $4 million, authorities say.

Abdi Salah was also benefiting from the scheme, federal authorities say. They allege that Abdi funneled more than $1 million from this scheme into shell companies that he used to purchase real estate, including a multi-family home with Sharmarke Issa, then the board chair of the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. Much of that money—at least $420,000—came from checks Abdikadir Mohamud sent to Stone Bridge Development LLC, a shell company Abdi created to launder food funds, authorities say.

Federal authorities also say that Abdi, along with Abdikadir Mohamud (who later joined the community safety workgroup) and three others, used federal food funds to purchase a former bar and restaurant in Brooklyn Park for $1 million.

Authorities charged Sharmarke Issa in a separate document not connected to Stigma-Free International. He operated food sites under both Feeding Our Future and another sponsor. But according to federal authorities, little of the funding went to feeding children. Altogether, Sharmarke is accused of defrauding the government of $7.4 million. According to authorities, he used the funds to purchase real estate.

‘Too close for comfort’

Mayor Jacob Frey declined to speak to Sahan Journal about the criminal allegations against his former staffer and appointees. But one of his former City Hall colleagues offered his observations about political leadership and relationships in Minneapolis.

Cam Gordon served 16 years on the Minneapolis City Council until losing his reelection bid to Robin Wonsley in November 2021. For eight of those years, he served alongside Jacob Frey, who was elected as a council member in 2013 and then as mayor in 2017. And for most of that time, Abdi Salah was there as a policy aide.

Gordon, who chaired the housing committee, recalled that Abdi fervently advocated for Sharmarke Issa to receive the position as board chair for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. The Minneapolis Public Housing Authority provides affordable housing to over 26,000 Minneapolis residents. The board oversees decisions about the agency’s budget and policy, and hires the executive director.

Sharmarke, a former public housing resident, held both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in urban planning. Gordon recalled that it was Abdi who had suggested Sharmarke should be named board chair. It isn’t a highly paid position; board members earn a stipend of $55 per meeting, for a maximum of $5,000 per year.

“I’d rarely seen Abdi Salah so motivated and engaged in things,” Gordon said.

Gordon said he supported Sharmarke for the position, hoping he would hold community meetings with public housing residents—which he did, Gordon said. The City Council confirmed Sharmarke to the post in 2019, before the alleged fraud began. He became the first Somali immigrant in the country to hold the position.

Though Gordon supported Sharmarke as Frey’s pick for board chair of the public housing authority, he opposed both of Frey’s mayoral runs. Gordon described the allegations against people he knew as “too close for comfort.” The Feeding Our Future connections to City Hall caused Gordon to reflect on the mayor’s leadership style.

“He’s very relational, this mayor,” Gordon said. “Relationships are important. If he has a trusted person, like Abdi Salah, he’s just going to be like, Okay, you’re an ally. I’ll follow you.” Sometimes those relationships have translated into political appointments, he said.

The connections between Frey’s circle and alleged food fraud, to Gordon, show “a mayor that isn’t as careful about picking who he works with or who he appoints.”

The mayor does not have oversight over federal food programs administered by the state. Still, David Schultz, a longtime political analyst who teaches law at Hamline University and the University of Minnesota, said the scope of the fraud and its connection to political figures raised questions about the way business gets done at City Hall.

“These may be people who have influence with the mayor, or the mayor may have influence over these people who get on the board,” Schultz said. Even though the mayor had no control over the food programs, connections with his circle could prove beneficial, Schultz explained. People committing the alleged fraud could use their relationships at City Hall to fend off inquiries and attempts at oversight.

For example, in May 2021, Frey and Jamal met with Minnesota Department of Education officials to discuss the food programs. Records show that Abdi Salah provided Frey with a list of talking points in advance of that meeting—which came directly from Feeding Our Future Executive Director Aimee Bock.

This influence could also manifest in a series of transactional favors, or patronage, Schultz said.

“You’ve got public officials who are doling out money to individuals and organizations. And in return, perhaps they are now doing political contributions or supporting the party in some way, shape, or form,” Schultz said.

At least eight people named in the indictment donated $1,000, the maximum allowable contribution, to Frey’s 2021 mayoral campaign. After six of those individuals’ names appeared in search warrants, Frey said he would return the campaign funds to the federal government.

Congresswoman Ilhan Omar, Attorney General Keith Ellison, and state Senator Omar Fateh also received campaign donations from some of the people implicated in the fraud. They said they planned to return the money or donate it to charity.