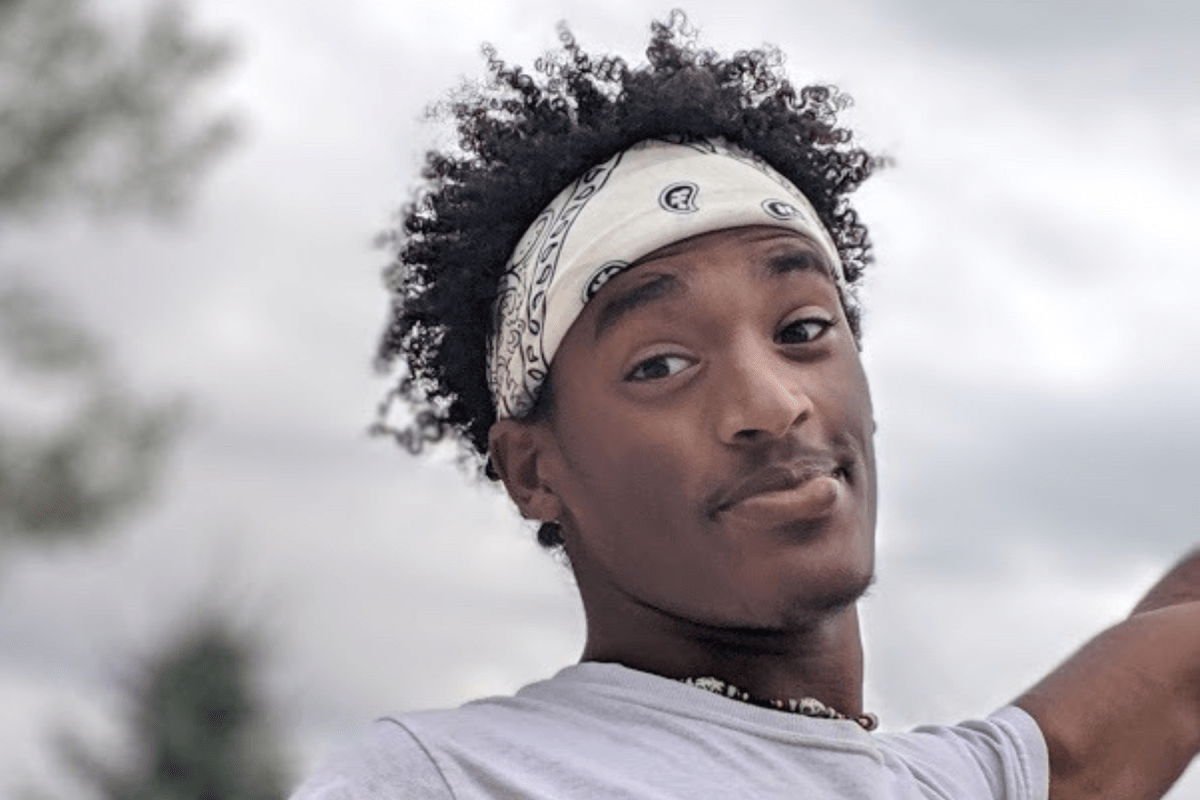

Tekle Sundberg’s friends are remembering him as deeply spiritual, a class clown, and a caring friend who helped loved ones through mental health problems even as he struggled with his own depression.

On July 14, Minneapolis police snipers killed Tekle at his south Minneapolis apartment building after a six-hour standoff that Tekle’s parents say was triggered by a mental health crisis. The standoff began after Tekle, 20, fired shots into a neighbor’s apartment, police have said. Body-camera footage released Wednesday shows police rescuing the neighbor and her children, but provides little visual insight into the moments before the snipers shot Tekle. In the recording, the snipers said they saw a gun just before they opened fire.

Sahan Journal reached out to Tekle’s family, which has granted just one media interview and issued one public statement since Tekle was killed, hoping to learn more about their son and brother. A family member said Tekle’s family would reach out to Sahan Journal if they felt ready to share.

Many of Tekle’s friends, however, did feel ready to speak. They want him to be remembered as a full, loving person—and as more than the worst moments of his life.

“He loved his life. He was an artist. He really made good meals. He loved his cat and his plants a lot. He would meditate every day,” said 19-year-old Jasmin De La Cruz. “He was very, very caring. He wanted to help people to see their true self. He wanted to help them reach their higher level that they didn’t ever see. He tried his hardest to be there for people who were really down on themselves.”

“Remember him as someone who always cared for the people he loved,” said Shimiah Vernon, 20. “Look at him as somebody who’s actually really strong for the stuff he’s been through.”

While initial news reports used his full name—Andrew Tekle Sundberg—his friends told Sahan Journal that the name he preferred was Tekle. For clarity, that’s the name used throughout this account.

Several of Tekle’s friends told Sahan Journal that he had helped them through serious mental health crises, even as he struggled with his own. They expressed worry about others in their friend group already dealing with mental health problems who now also must grapple with the trauma of Tekle’s death.

“He was an advocate for mental health, always telling people about how important it was,” said Marie Peterson, a 20-year-old rising junior at Macalester College in St. Paul. “He also was such an advocate for the Black Lives Matter movement. So for him to get murdered at the hands of the police for mental health was just heartbreaking and disgusting, horrifying to me.”

‘He always had a joke for everything’

The first time Miya Moore met Tekle, he was off by himself at recess, drawing. The other kids at Upper Mississippi Academy had told her Tekle was weird, but Moore didn’t care. She asked what he was drawing. Before long, the two became close friends. He was her “first love,” Moore said.

As teenagers, they often sat and smoked, climbing trees and playing tag. “He just brought that inner child out of me,” she said.

At Roosevelt High School, he became known for his jokes and his agility on the wrestling team.

“He was such a goofball,” Peterson said. “The epitome of class clown.”

“He always had a joke for everything,” recalled Vernon. “Sometimes the teachers would be like, ‘OK, Tekle, it’s time to stop playing, we have to get serious.’ But he was always the person in class who just made everyone laugh.”

Moore, who’s now in California attending acting school, recounted a prank in which Tekle filled his hand with flour to playfully smack a friend, leaving the white powder on their face.

“If you were sad, he would come to you and find a reason to get you to smile,” she said. “There was never a time that I was around him that I wasn’t laughing.”

“There was never a time when I was around him that I wasn’t laughing.”

Miya Moore

Tekle didn’t care what others thought about him, his friends recalled.

“He just wanted to be himself,” Vernon said. “He didn’t want to fit in with nobody who didn’t want to accept him. He wasn’t going out of his way to try to make friends. He just let people gravitate towards him.”

At times, he was a rebellious kid, Moore recalled. She FaceTimed him once to find him tagging a building with graffiti. “I was yelling at him through the phone,” she said. “I was like, ‘Would you please stop? Are you an idiot?’ And he was like, ‘Dude, stop. You’re gonna alert the police.’” On another occasion, he stole a stop sign, she said.

The first time he met her younger sister, she said, he performed a Naruto run, an anime meme, in which he stretched his arms out and ran partway up a wall.

He also defended other kids from bullies. When a classmate appeared different from others, he’d explain their behavior to his friends, Moore said.

“He was one of the most articulate, intelligent, kind-hearted, motivated—regardless of his mental health issues—funny, artistic people I’ve ever known in my life,” she said.

‘He was always there for me, whatever I was going through’

When Markeanna Dionne told Tekle she wanted to quit the Roosevelt wrestling team, he talked her out of it.

As a freshman, Dionne said, she didn’t feel like she belonged on the team. The headgear and the uniform didn’t fit, and she didn’t know what to do with her hair. And she was one of only two girls on the team. She told Tekle, then a junior, that she wanted to quit.

“He’s like, ‘If you quit, I’m gonna fight you,’” she recalled with a laugh.

His encouragement came to mean a lot to Dionne.

“I didn’t grow up with a lot of support,” she said. “It felt good to have someone, know that they believed in me.”

Dionne struggled with depression and self-harming. One day at wrestling practice, Tekle noticed marks on her arm and asked her about them. “What do you do to cope?” he pressed her.

When she started sharing her own poetry on social media, he cheered her on. Tekle’s support helped develop Dionne’s confidence—and helped her through some difficult mental health struggles, she said.

Peterson, the other girl on the wrestling team—and the teammate who recruited Tekle to join—also found him to be an invaluable source of support.

“He was always there for me, whatever I was going through,” she said. “Injuries with wrestling, eating disorders, my own mental health problems. Issues of substance abuse, even breakups—he was a rock through all that.”

‘He was basically my therapist’

Tekle was born in Ethiopia and adopted by a Minnesota family. Peterson, also an adoptee, said that for both of them, adoption was an early trauma.

“He could relate to a lot of things that I was going through,” Peterson said. “I could relate to a lot of things that he had been through.”

“He loved his family dearly,” Moore said. “They were really sweet to him, and they gave him the best upbringing possible. He just still had questions about his origination.”

For Moore, too, Tekle was a key source of mental health support. When she was hospitalized after a suicide attempt, she sneaked her phone in to talk to Tekle.

“I was out before the rest of the kids because he was basically my therapist,” she said. “Just having him there even in a virtual way was helping me.”

‘He would break down in front of me’

Since Tekle had moved into his own apartment, friends say, he was focused on himself, his spirituality, his cat, and his plants. He had graduated with the Roosevelt class of 2020, which did not have a graduation ceremony or prom due to COVID-19. But he stayed in touch with his friends on social media, over the phone, and in person.

“He was always telling me how he’s focusing on his meditation, his spiritual journey, his fitness,” Peterson said. Tekle often ran 10 miles a day, and if he was injured, he would bike 20, she said.

Dionne, who lived near Tekle, sometimes ran into him at the light-rail stop. She’d see him talking to or dancing with homeless people.

Tekle’s spirituality, which Moore describes as similar to her own, revolved around energy, including the law of attraction. This concept stipulates that the energy and thoughts a person puts into the world will come back to them, and that positive thinking can generate a more positive reality.

But Tekle was struggling with his own mental health problems. Peterson and Moore both described him as “depressive,” and said that at times he struggled to maintain the will to live.

“[Police] shouldn’t get to decide if you live or die. He was a really sweet person, and he deserved to heal himself.”

Markeanna Dionne

Several friends wondered if he wanted to die the night of the standoff with police.

“He told me a lot of the things that were going on in his head a lot of the time,” Moore said. “He would break down in front of me. We had a lot of sincerely emotional conversations, and I just knew that he had a lot going on.”

Peterson believes that in his last few months, Tekle had been largely by himself. They spent less time together as she got busy with college. But this spring, he told her she was the first person he had really talked to in months. Soon after that, though, he told her he wanted to take some space from her. She knew he had had a similar conversation with someone else close to him.

“He was really focused on himself and his own spiritual journey,” she said. “I would never want to get in the way of someone’s self-growth. I thought that was what was best for him at the time. So I didn’t mind taking a step back.”

Instead of spending time with people, he posted more and more videos on social media, Peterson said.

Over the last six months, his videos made Vernon think that Tekle was not “in his right state of mind.”

His recent videos did not make sense to her, Vernon said. “But I could tell in his video he had a straight point he was trying to get across, where it made sense to him.” That communication style struck her as out of character, she said.

Peterson knew that Tekle had acquired a gun for self-defense. But she does not believe he would have fired it unless he felt physically, mentally, or emotionally in danger.

Tekle’s last messages

After the news ran through their group that Tekle had been killed by police, his friends pulled up his social media accounts to see what they could learn. They found a series of Snapchat videos from the night of the standoff.

“He was at home in his window,” Vernon said. “You could see all the police outside. They had all their guns pointing up towards his window.”

Tekle spoke through each video, but only the beginning of the first video captured sound, she said. After that, no audio could be heard.

“Basically he was talking about, it’s crazy,” she recalled. “Then you hear him say ‘me and them’ and then the video cut off. You couldn’t hear anything else after that.”

She thinks “me and them” was probably referring to police. None of their friends knows why the videos were muted, and because Snapchat videos disappear 24 hours after posting, they are no longer available.

His pupils were so big, Vernon recalled. He looked scared. “I could see in his eyes that he just didn’t look like Tekle,” she said.

“People should check on the people that they love. The people they don’t love. Sometimes people just need to be asked if they’re OK.”

Shimiah Vernon

Moore, too, believes Tekle was not himself that night. To her, the body camera footage makes it appear that he was either on drugs—though to her knowledge, he only smoked marijuana here and there—or was having a mental breakdown. She questions whether he had the will to live that night. But that does not excuse the police decision to kill him, she said.

“They shouldn’t get to decide whether you live or die,” Dionne said. “He was a really sweet person, and he deserved to heal himself.”

Vernon hopes Tekle’s death can help bring more awareness to mental health issues for Black men.

“People should check on the people that they love,” she said. “The people they don’t love. Sometimes people just need to be asked if they’re OK.”

But that awareness won’t bring back the friend who was there for them in hard times, and always made others laugh.

“You’ll never meet somebody like Tekle,” Vernon said.

If you or a loved one needs mental health support, help is available.

—Call or text 988, the new national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, starting July 16.

—Throughout Minnesota, call CRISIS, 274747, to be connected to your county’s mobile crisis team. These calls are answered 24/7. You can also text MN to 741741.

—Canopy provides culturally informed therapy services to historically marginalized communities in the Twin Cities. You can call 612-712-7200.