Jaida Grey Eagle became fascinated with the history of photography and its impact on Indigenous communities while she was a fine arts student at the Institute of American Indian Arts in New Mexico.

The institute’s library had no deficit of Native scholarship and art, but Grey Eagle found slim pickings in the photography section.

“I was like, ‘I want more. And I want something now,’” she said.

She began curating work by Native photographers for her graduation project.

“If somebody like me is searching for something like this, there are others who are searching for something like this,” she said.

After she graduated in 2019, curators at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) began chatting with Grey Eagle about collaborating together on an exhibition.* She described the project as for, by, and of Native people. When it came to supporting the project, the museum was sold.

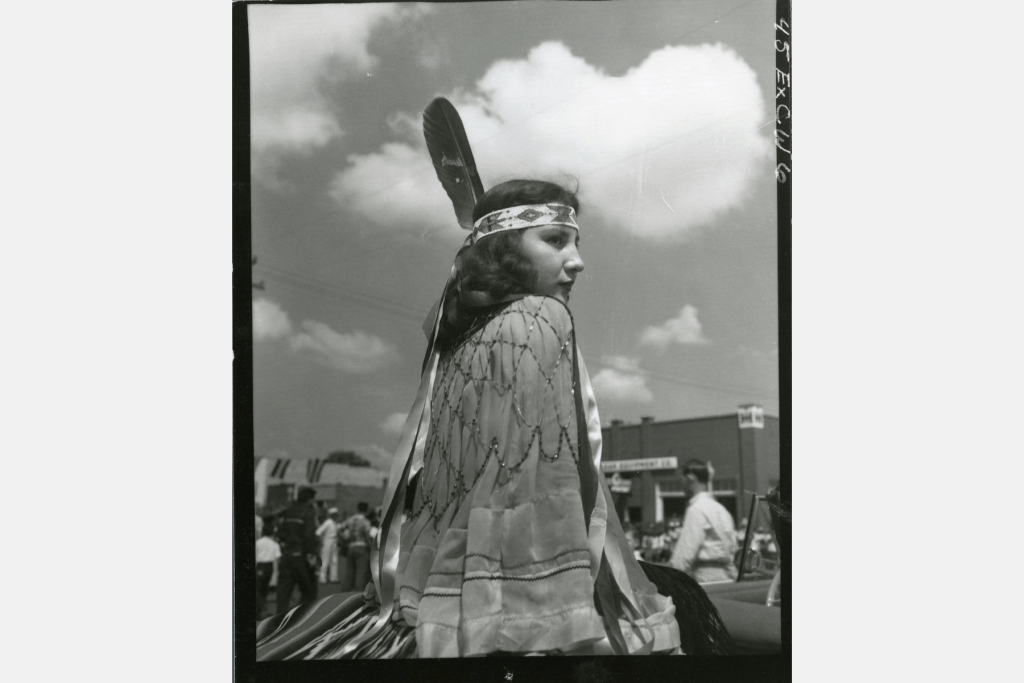

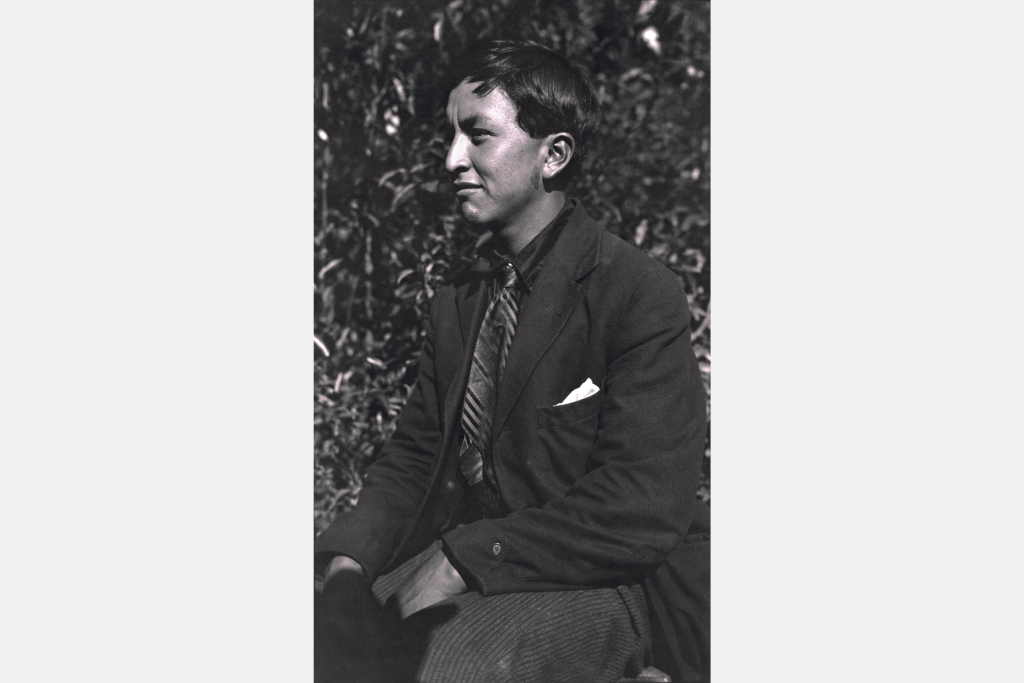

The Minneapolis Institute of Art will open “In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now” on October 21, displaying a collection of more than 150 photographs of Indigenous people through the lens of Native photographers. The exhibition showcases Native photographers from the early days of photography to today, and follows the intersecting histories of Indigenous people, including First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and Native American cultures “from the Rio Grande to the Arctic Circle.”

The curators said this is the museum’s first exhibition exclusively featuring photography of Native people by Native photographers.

The exhibition, which is ticketed, will run through January 14, and will feature an opening night party on October 21, an artist talk with Grey Eagle on December 3, and free admission days for museum members. Admission to the show is $20.

Sepia tone to neon pink

Grey Eagle, 35, is a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe originally from Pine Ridge, South Dakota. She’s a photojournalist, producer, beadwork artist, and writer, and has worked for Sahan Journal.

Grey Eagle calls the East Side of St. Paul home, and grew up in Red Wing, south Minneapolis, and West St. Paul. As a child, she used to take photos of her family using her parents’ camera. Grey Eagle continued to nurture her passion with each new camera her parents purchased.

“I just want people to know that communities are more than capable of telling their own story—and they always have been,” Grey Eagle told me at Mia’s photographs study room on a recent afternoon.

A book compiling photographs from the exhibition sat on a large table in front of her—the kind of book she had looked for in her college library so many years ago.

“We’ve been told that this exhibition should have happened a long time ago, and it’s unfortunate that it didn’t,” Grey Eagle said. “I would have really benefited from it happening a long time ago. But I mean, it’s happening now.”

As a guest curator, Grey Eagle worked with two Mia curators, Casey Riley and Jill Ahlberg Yohe, and a curatorial council of 14 people, including Native artists, academics, and what the curators call “knowledge-sharers” based in Canada and the U.S. The curatorial council helped develop a checklist and thematic organization for the show.

“What we learned in speaking to a couple of elders on the council—collectively, Jaida, Jill, and I brought a limited amount of knowledge,” said Riley, the museum’s chair of global contemporary art and curator of photography and new media. “And yet there was this whole world, this whole self-sustaining ecosystem of knowledge and practice that had been overlooked by mainstream scholarship and museums for a very long time.”

Ahlberg Yohe is the museum’s associate curator of Native American Art.

The exhibition is split into three thematic sections: “A World of Relations,” reveals the ways Native people connect with the living world holistically. “Always Leaders” recognizes Native leadership in an array of social issues. “Always Present” celebrates the Native photographers and rejects harmful visual narratives of Native communities.

“It really showcases our commitment to working in collaboration with the Native communities to showcase their contribution, specifically to photography in this exhibition, but to show their contributions to art,” said Molly Lax, the museum’s media and public relations manager.

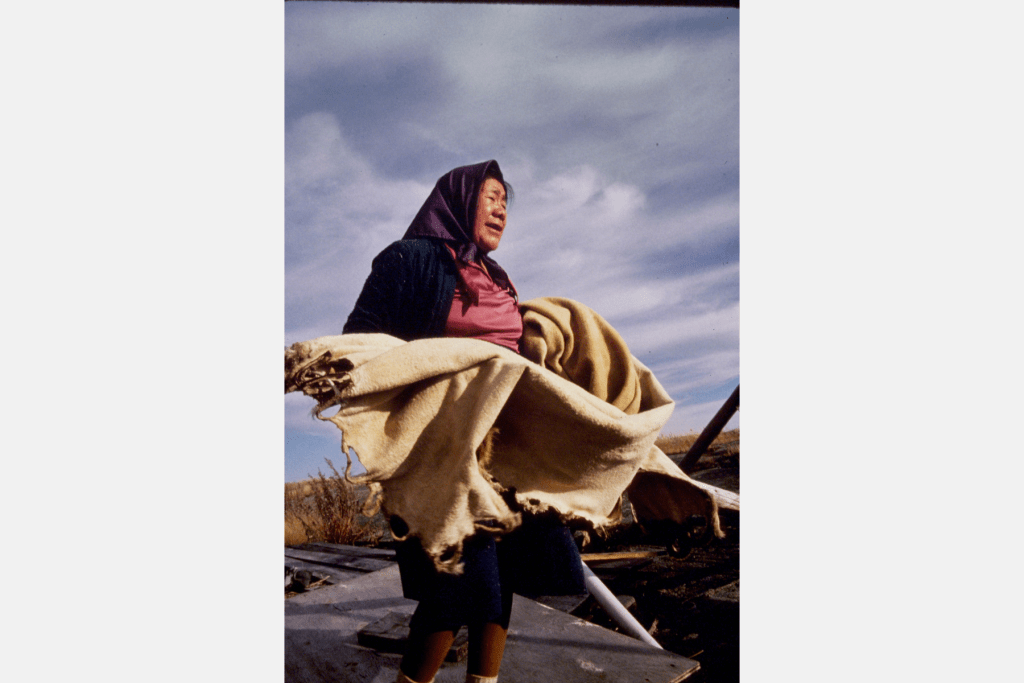

The photos in the exhibition span more than 100 years. There is fine art photography, portraits, photojournalism, historical black-and-white and sepia shots, multimedia photos with beadwork, and personal projects.

The exhibition features photographers like Horace Poolaw, who is a member of the Kiowa tribe. He photographed a series of portraits in 20th-century Oklahoma. One of his earliest pieces was a hand-colored portrait of his father taken around 1930.

The exhibition also includes photographer Shelley Niro, whose piece from 1991, “The Iroquois is a Highly Developed Matriarchal Society,” depicts her mother under a hooded hair dryer in Niro’s sister’s kitchen. Her sister was training to be a hairstylist. The piece, which consists of three photos, is subtly tinted with bright yellow and neon pink.

“By relying on Native knowledge systems to guide their work, the many curators who have contributed to this project have advanced the work of Mia as a whole,” Mia President Katie Luber said in a news release. “This exhibition underscores both our long-standing commitment to presenting works by Native artists and how our approach with these artists can strengthen relationships with our audiences and community.”

Three years in the making

Grey Eagle and her co-curators installed the exhibit in mid-October in Mia’s 12,000-square-foot Target gallery. Grey Eagle and Riley joked about conversations they’ve had with people who assumed that the exhibition was going into the museum’s smaller galleries.

“It’s in the largest galleries here. It’s quite big,” Grey Eagle said. “People wouldn’t grasp what I was saying.”

Grey Eagle and Riley sat across from me at a large table in a room where the museum archives its photography collection, books filling every corner of the warm, light-filled room.

“It’s so interesting to go elsewhere and see the way in which photography is documented,” Grey Eagle said, waving her hands towards the large shelves behind her filled with books about photography.

Grey Eagle and I started working at Sahan Journal at the same time in 2020. We drove to events and interviews together. At a time when Sahan’s staff—and the rest of the world—was still working remote because of COVID-19, I got to know Grey Eagle in her car, where she told me about all the projects she was working on, along with the constant string of assignments coming from our editors in Sahan’s early days. I always wondered how she found enough hours in the day.

One of the projects she told me about three years ago was this very exhibition.

Riley said she, Grey Eagle, and Ahlberg Yohe began talking about the project in March 2020. They held their first curatorial council meeting in October of that year after a series of conversations with board members and after receiving support from the museum. By mid-2021, the work was in full swing.

“It was a very lengthy process of getting all the information, putting it to a vote, reaching out to the artists and the galleries and the institutions, getting the loans,” Riley said of obtaining the photographs on loan. “In the meantime, we also formed a community council in the final year of the project.”

The community council was a separate entity of nine members representing tribes in Minnesota and surrounding areas who advised the curators about how to take the exhibition out of the museum and into the community.

Asked about her role in putting the exhibition together, Grey Eagle said: “I don’t ever want to focus this project on me, because it’s so many people coming together to create it.”

I prepared to tease more out of Grey Eagle, who I’ve known to answer any question about herself with a soft-spoken humility.

Grey Eagle listed some of her tasks: she wrote labels for the work, helped edit the book for the exhibit. Over the summer, she worked with the museum’s media team to film interviews with the curatorial council and featured photographers. She also traveled to Santa Fe, Toronto, and Wisconsin to meet the photographers.

“I came in last week and had to record an audio tour,” Grey Eagle added.

“So, there’s an audio tour? With your voice?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said with a soft laugh as I screamed excitedly.

“I have to interject here and say Jaida’s being modest,” Riley said. “The whole reason this project exists is because of Jaida.”

“I’ve learned a lot from Jaida about what it’s like to be an artist in your 30s working in Native circles, and all of the responsibilities and complexities and joys of doing that work,” Riley added.

“I’m dying on the inside right now,” Grey Eagle said laughing.

We ended our conversation by flipping through the photography book in front of us as Grey Eagle picked a piece to tell me about.

She selected a few photographs by Dorothy Chocolate Carseen documenting elders teaching people about working with animal hide. Grey Eagle told me Chocolate Carseen self-funded trips to photograph Native culture camps.

“I found it to be so beautiful,” Grey Eagle said of the photographs. “They’re so rooted in this incredible life-way, and it’s just pushing culture and her fortitude to document that.”

Grey Eagle said she views Indigenous photographers like herself as artists who think a lot about the future and preserving who they are for future generations.

“And that’s what these say to me,” she said gently tapping on the page. “She’s thinking about those people that are coming after her.”

In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now

When: October 22, 2023 to January 14, 2024

Where: Minneapolis Institute of Art, Target Gallery, 2400 3rd Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55404

Cost: General Admission $20, free for Contributor Member+ (additional tickets $16), free for youth 17 and under

More: October 21, 2023

- Opening conversation with curators and curatorial council from 11 a.m. to 3:45 p.m.

- Preview party, an after-hours party in the galleries, 8 p.m.

December 3, 2023

- Artist talk with Jaida Grey Eagle, a lecture and conversation on her multidisciplinary artistic practice, at 2 p.m.

*Clarification: This story has been edited to more clearly explain the inception of the exhibition as a collaboration between the three curators involved.