When the Minnesota Legislature passed a law in May boosting protections for diverse, historically polluted neighborhoods, it marked the end of a years-long effort by environmental justice advocates and lawmakers.

But the bill’s passage was only the beginning for the Frontline Communities Protection Act, broadly known as the cumulative impact law. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) hosted an open house in St. Paul Thursday evening aimed at developing the law, which will go into effect in April 2026.

Anna Hotz, who leads administrative rulemaking at the MPCA, said the state will need help from the public to formally define key terms in the bill. The cumulative impact law seeks to enforce higher regulatory standards for businesses and industries that want to operate in historically polluted neighborhoods. Racist zoning and housing policies built a system in which communities of color face higher levels of pollution, according to state data.

“Today, as a result, too many children are disproportionately exposed to harmful pollution,” Hotz said.

Environmental advocates are excited about the law and its potential to help frontline communities. They want to be an active part of the rulemaking process.

“I think it’s important that the next three years are closely watched,” said B Rosas, who works with the nonprofit Climate Generation.

Time to define

The cumulative impact law will require the MPCA to consider total and historical levels of pollution when it considers issuing new permits or renewing existing ones in neighborhoods that have been labeled environmental justice areas. Such areas are defined as places where one or more of these conditions are met:

- More than 40 percent of residents are people of color.

- Thirty-five percent of the population is at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, which is defined as a household income of about $60,000 for a family of four.

- Forty percent of the population has limited English language skills.

- The area is located on a federally recognized Tribal Nation.

There are 123 existing facilities with permits that now fall under the law, according to the MPCA. There are roughly 2,000 air pollution permits in Minnesota.

Of the current facilities, 68 have permits that expire every five years and would be impacted by the law automatically; 55 have non-expiring permits and would only come under the law if they sought to expand.

RELATED STORIES

Historically, the MPCA considered all permit applications on an individual basis and allowed businesses to produce emissions within levels the state had predetermined was acceptable for facilities of their kind. Such businesses could include landfills, foundries, or power plants, among many others.

Now, projects proposed in or near environmental justice areas could trigger an analysis of how they contribute to overall pollution before the MPCA determines whether they should be allowed to operate.

But the law has several terms and components that need to be defined before it can take effect, Hotz said. That includes determining what pollution benchmarks would trigger a cumulative impact analysis, what constitutes a substantial adverse health and environmental impact, and what factors would be considered environmental stressors.

The law allows for projects that create pollution in environmental justice areas to proceed if the project enters a community benefit agreement with residents in the area. But the law doesn’t define what constitutes such an agreement, how much neighborhood support is required to move forward, or how to measure if a majority of residents support it.

Although initially proposed to cover the whole state, the cumulative impact law only applies to Rochester, Duluth, and the seven-county Twin Cities metropolitan area (Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, and Washington counties).

Large swaths of the three areas are considered environmental areas or fall within the mile buffer range established in the law, according to the MPCA. That includes about half of the metro area, half of Rochester, and two-thirds of Duluth, Hotz said.

Steve Pak, an air permitting manager with the MPCA, said the law is a clear message that the agency needs to be more intentional when approving permits and hold more open meetings with the community.

The MPCA is formally requesting comments from residents on those definitions through October 6. You can submit comments here.

Staying engaged

Several Minnesota organizations and residents of environmental justice areas advocated for the cumulative impact bill. With its passage, many are gearing up to keep the pressure on the MPCA to create strong protections for polluted neighborhoods.

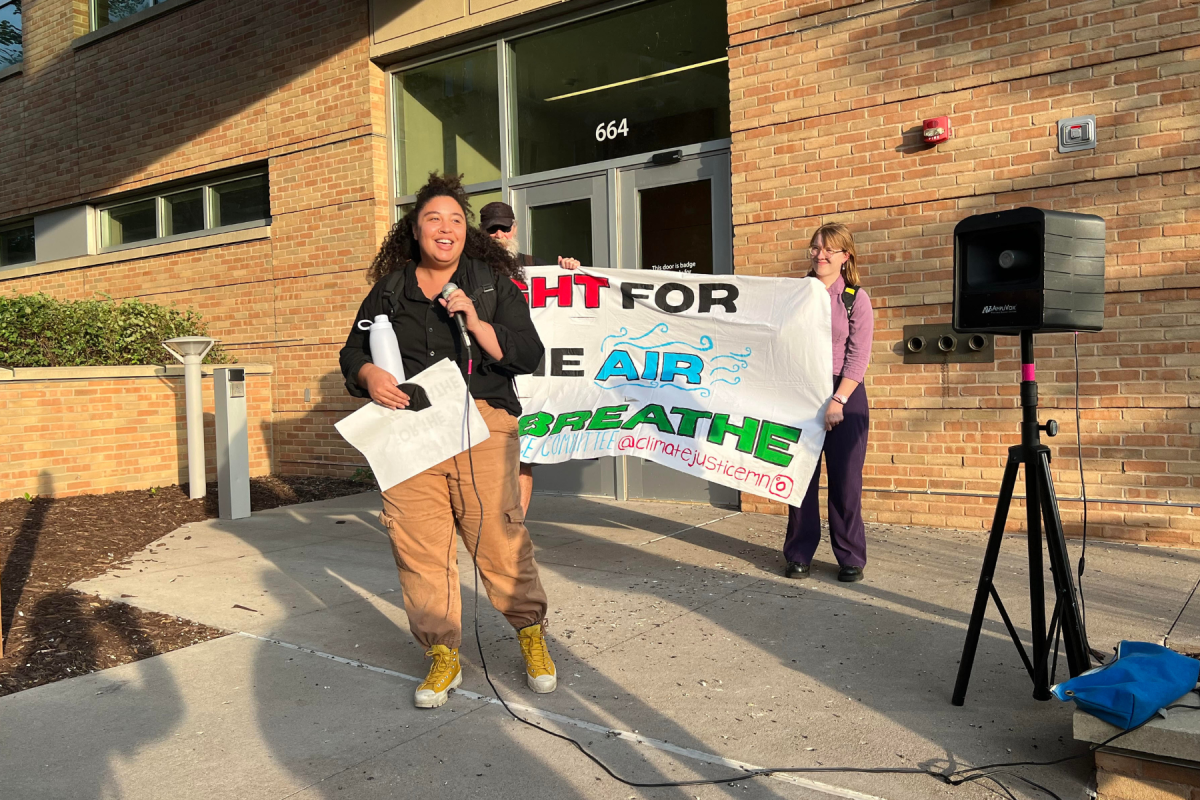

Outside Thursday’s meeting at Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, residents representing several climate groups pledged to stay involved through the rulemaking process.

The rulemaking process is more than a celebration; it’s a moment to read the bill and get involved, said Sophia Benrud of the Minnesota Environmental Justice Table.

“All pollution is too much pollution for us to experience,” Benrud said.

Kawakatalt, with the American Indian Movement, said the MPCA should be consulting the Dakota Nation about policies that impact Dakota homelands.

“At a minimum, you should have a Dakota representative here,” he said at Tuesday’s meeting. “Shame on you. You have a gargantuan task.”

Kawakatalt said he wanted to challenge state officials to remember that they have a responsibility to the land and to honor Native rights.

As the MPCA’s presentation came to a close, it became clear that environmentalists view the agency with skepticism. The agency’s approval of the Line 3 crude oil pipeline through northern Minnesota disappointed many.

Several people at the meeting pointed out that the 2008 cumulative impact law established for the Phillips neighborhood of south Minneapolis hasn’t led to major changes for facilities like Smith Foundry or Abbott Northwestern hospital.

Staff from the MPCA said the new law will give them more tools to protect residents from pollution, and that they’re concentrating on making it effective instead of focusing on the past.

How to submit your thoughts on the cumulative impact law:

What: The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) is asking for public feedback on how to define and enforce the Frontline Communities Protection Act, broadly known as the cumulative impact law.

How: You can submit comments online here until October 6, 2023.

Meetings: The MPCA is also hosting three more public meetings in Brooklyn Center, Duluth, and Rochester about the law. The meetings are all scheduled in September. Find more information about the dates, times, and locations here.