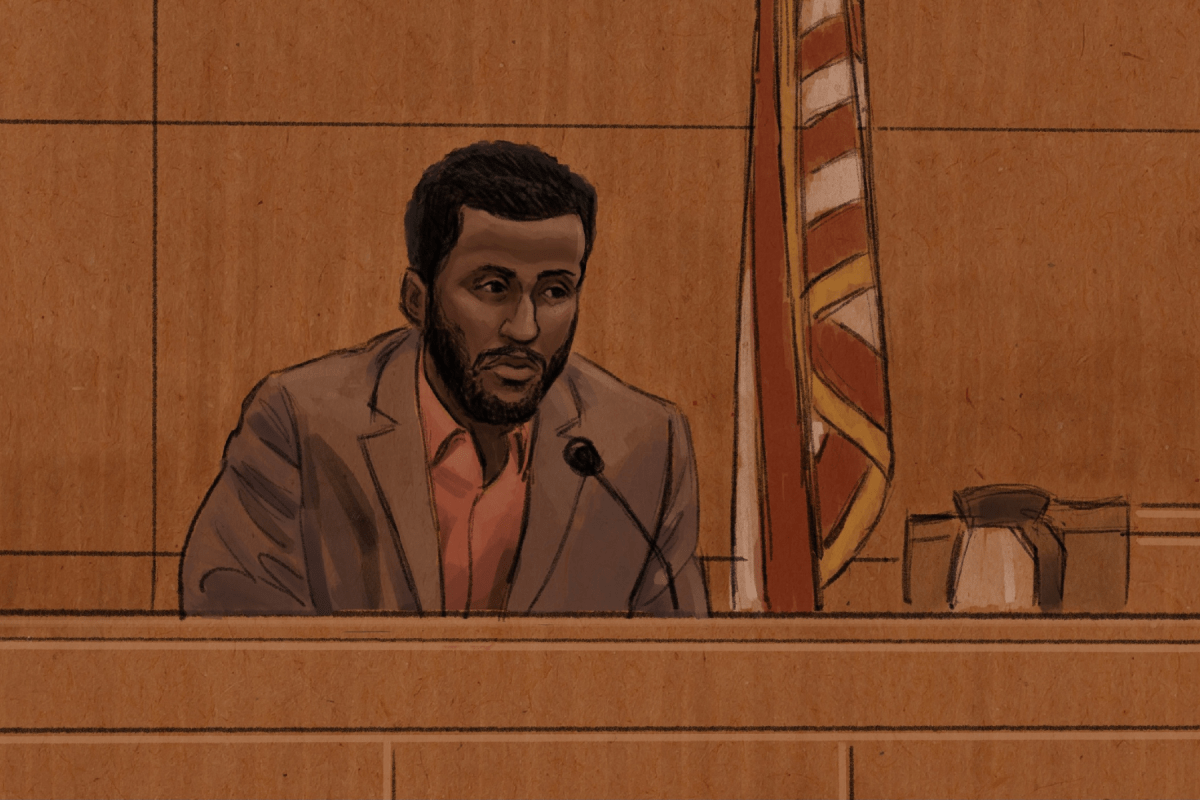

A former Feeding Our Future employee revealed explosive new information in court Wednesday about alleged fraud and “chaos” at the organization, and a threat he received from its lawyer. He also testified that he created a shell company that committed more than $1 million worth of fraud, and that he received kickbacks for his work at the nonprofit.

Hadith Ahmed, 34, a former site supervisor for Feeding Our Future, described himself as “Aimee Bock’s right hand man,” referring to the executive director. He testified that he participated in a federal program that reimbursed people for feeding underserved children in order “to get rich.”

“I think the best way to put it is, Feeding Our Future was like a bank,” Hadith said. “You come and you get the money.”

Hadith testified in the third week of trial for seven defendants who allegedly falsely reported the number of meals they served children in order to receive federal funding. They face a total of 41 criminal charges, including money laundering, fraud, and bribery.

Hadith’s testimony is the first time jurors have heard from someone who was employed by Feeding Our Future, which is at the center of a $250 million fraud investigation.

Hadith described Feeding Our Future as the “crazy” anchor for widespread fraud that involved more than 200 people. He called the atmosphere there “chaos.”

Hadith testified that Bock fired him in the fall of 2021, a day after he told a woman he would not submit her reports, known as “meal claims,” for the number of meals she said she served over several months.

The day after he was fired, Hadith testified, Bock and her attorney called him and warned him not to speak with authorities about Feeding Our Future. Bock and her lawyer, who was not named during testimony, told Hadith they knew about the kickbacks he received, Hadith testified.

“He threatened me that if I go to the government and say anything about Feeding Our Future, they would go after me,” Hadith said of Bock’s lawyer at the time.

In a brief phone call with Sahan Journal Wednesday afternoon, attorney Rhyydid Watkins, who represented Feeding Our Future in a 2020 lawsuit related to the federal program, declined to comment on Hadith’s testimony.

Bock was indicted in the case in 2022, and is being represented by attorney Kenneth Udoibok. It would be “far fetched” to believe that any defense lawyer would make the comments in Hadith’s testimony, he said in an interview with Sahan Journal.

“I don’t make those kinds of comments,” Udoibok said.

The defendants are being jointly tried for allegedly stealing $40 million from the federal Child Nutrition Program by inflating the number of children they fed—or by reporting to feed children when they served none at all. The suspects allegedly shuffled the money through shell companies and used it to buy flashy cars, lavish vacations, and luxury real estate, among other purchases.

The case is part of a much larger investigation federal prosecutors have described as the nation’s largest COVID-19 fraud against the government. Seventy people were charged in the case; 18 defendants, including Hadith, have pleaded guilty and await sentencing.

The Minnesota Department of Education distributed the federal funds to sponsor organizations like Feeding Our Future and Partners in Quality Care. The sponsor organizations then dispersed those funds to food vendors and food sites, which were supposed to provide ready-to-eat meals to local children.

Several organizations reported serving thousands more meals than they actually did—or simply never served any meals at all—in order to receive more federal money, according to prosecutors. Those funds were then allegedly passed through various shell companies before being pocketed by the perpetrators.

The sponsor organizations were supposed to vet the number of meals the vendors and sites reported serving before sharing that information with the education department.

Food sites rarely visited

Hadith said he was in charge of other supervisors who were supposed to visit food sites to ensure they were feeding children. Hadith testified that the supervisors rarely visited the sites, and that he received pushback from staff when he attempted to send supervisors to the sites or attempted to visit some himself.

“I didn’t do anything,” Hadith said of fulfilling his job responsibilities. “I just started getting kickbacks.”

Hadith testified that when he was at Feeding Our Future, roughly 200 people worked for purported food sites and were submitting claims to the organization at frequent and high rates. The claims listed the number of meals they reported serving.

Before working for Feeding Our Future, Hadith testified, he worked as a director of a childcare center in Eden Prairie called Delta Learning Child Care Center. He was in charge of day-to-day operations, enrolling families, and hiring staff. He also billed the government for various programs, including the federal Child Nutrition Program, in support of the daycare.

Under questioning from prosecutors, he said he first enrolled Delta in the program through Partners in Quality Care in 2018, feeding roughly 25 to 40 children a day. The government would reimburse the daycare center between $3,000 to $5,000 per month for the meals.

“Were you getting rich?” U.S. Assistant Attorney Harry Jacobs asked Hadith about the reimbursements at Delta.

“No,” Hadith responded.

Hadith said he met Bock in 2019, and eventually switched to using Feeding Our Future as a sponsor for Delta’s meals.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the daycare center closed and Hadith was out of a job.

“There was no income, there was no kids—nothing was going on,” he said.

He testified that Bock offered him a job at Feeding Our Future, where he officially started in the fall of 2020.

It wasn’t long before Hadith realized business at Feeding Our Future was booming. On some days, as many as 20 to 30 applications for new food sites were coming into the nonprofit, Hadith testified. Some were from truck drivers who never worked in childcare.

“At that time, Feeding Our Future was crazy,” he said. “Everyone was submitting applications with Feeding Our Future, whether they worked with children or never worked with children.”

Eventually, Hadith said, he wanted a piece of the pie for himself, so he created a shell company called Southwest Metro Youth with the help of Feeding Our Future employee Abdikerm Eidleh. Hadith used the address of his Eden Prairie apartment to register the business as a food site that falsely claimed to serve meals. Hadith registered Southwest Metro Youth into the federal meals program through Feeding Our Future.

“Why did you want to participate in Feeding Our Future?” Jacobs asked.

“To get rich,” Hadith said. “To make money.”

Over the course of six months, Hadith testified, he operated Southwest Metro Youth as a fake food site and stole more than $1 million from the government.

Hadith testified that he also found a way to make money through his job at Feeding Our Future: He gave preferential treatment to some food sites in exchange for kickbacks, earning himself another $1 million.

Hadith testified that he used the money to buy a $600,000 house in Savage and property in Kenya. He said that several people who were part of the fraud posted photos on social media to show off their lavish purchases.

Hadith said he ensured that meal claims for some food sites were among the first Bock reviewed for approval, which helped them receive payment sooner. He testified that he also promised them that their sites wouldn’t be visited by staffers.

“This was VIP treatment,” Hadith said.

He testified to receiving kickbacks from Empire Cuisine, a food vendor that reported providing food to a food site at Dar Al Farooq, a mosque in Bloomington. He testified to receiving kickbacks from other businesses as well. A prosecutor presented emails in court showing that Hadith helped Mukhtar Shariff, a defendant in the trial, change the food site’s sponsor from Partners in Quality Care to Feeding Our Future. The change came after Bock met with Abdiaziz Farah, a defendant in the trial, Hadith testified.

Bock and Kara Lomen, the executive director of Partners in Quality Care, were competing for food sites and held a grudge against each other, Hadith testified. Mosques in particular were desired as food sites, Hadith said, because they have high foot traffic and are preexisting nonprofits that don’t have to be registered.

“You can exaggerate the number,” Hadith said about reporting meals served at mosques.

The Dar Al Farooq food site was operated by Mind Foundry, an alleged shell company started by Mahad Ibrahim, a defendant in the case who is not a part of the current trial. The company’s alleged food supplier was Empire Cuisine and Market, a restaurant owned by two defendants in the trial, Abdiaziz Farah and Mohamed Jama Ismail.

Prosecutors presented a $10,000 check in court that was written from Empire to Hadith for “consulting.” Hadith testified that it was a kickback to ensure that the Dar Al Farooq site would receive preferential treatment at Feeding Our Future.

Prosecutors showed similar alleged kickback checks written to Hadith from Bushra Wholesalers, which was owned by defendants Said Farah and Abdiwahab Aftin.

Feeding Our Future executive director ‘didn’t care’

Hadith also testified that in the spring of 2021, the Minnesota Department of Education started requiring sponsor organizations like Feeding Our Future to start submitting documentation to support the meal claims they were submitting. This prompted the defendants and others to start creating and submitting fake rosters of children and fake invoices for food, he testified.

At one point, Hadith said, he and Bock determined that multiple sites were submitting the same childrens’ names in their rosters.

“She didn’t care,” he said of Bock. “We knew that the names were fake because they all matched, and every week it was the same list of names. We didn’t say anything. We just let it go.”

“Why?” Jacobs asked.

“If Aimee said let it go, who can say anything about it?” Hadith responded.

Hadith testified that after he was fired from Feeding Our Future, he took a similar job for The Free Minded Institute. That company was run by Julius Scarver, who Hadith testified was Lomen’s boyfriend and “right hand man—just like I was for Aimee Bock.” The fraud continued at the institute, Hadith said, adding that Empire Cuisine and ThinkTech Act were participants.

In January 2022, FBI agents raided two dozen properties associated with the case, making its months-long investigation into Feeding Our Future public. Hadith testified that he panicked, and eventually met with Abdiwahab Aftin, a defendant in the trial, and came up with a plan to create a new company, Mizal Consulting. The two forged a fake consulting agreement between Mizal and Empire Cuisine, Hadith said.

“I was scared,” Hadith said. “And I think everyone was scared, and we just wanted to make sure it looked like a contract.”

“Why were you scared,” Jacobs asked.

“Because I was stealing money from the government,” Hadith said.

FBI agents contacted Hadith in June 2022, and he agreed to cooperate with the federal investigation after consulting with his lawyer.

Hadith was charged with a felony of information in the case in September 2022, and pleaded guilty to one count of wire fraud that October. He is awaiting sentencing.

Defense attorney Steve Schleicher, who is representing Said Farah, began cross examining Hadith late Wednesday, and accused him of refusing to cooperate with the government until he was caught.

“The government reached out to me, and I was shown the paper trails, and it was obvious,” Hadith said.

“We’ll get to the obviousness of your criminal activity later,” Schleicher said.

Hadith’s testimony resumes Thursday. The trial began April 22, and is expected to last until the end of May or mid-June.

Staff writer Andrew Hazzard contributed reporting to this story.

Correction: The story has been updated to reflect that Hadith Ahmed received kickbacks from Empire Cuisine, a vendor that supplied meals to a food site at Dar al Farooq.

Who’s on trial?

The defendants on trial are facing a total of 41 charges, including wire fraud, bribery and money laundering. They mostly worked for businesses that used Partners in Quality Care as a sponsor.

The defendants are:

- Abdiaziz Farah co-owned Empire Cuisine and Market. Federal prosecutors allege that the Shakopee-based deli and grocery store posed as a meals provider for several food sites, and defrauded the government out of $28 million. Abdiaziz allegedly pocketed more than $8 million for himself. He is also charged with lying on an application to renew his passport after federal agents seized his passport as part of their investigation.

- Mohamed Jama Ismail co-owned Empire Cuisine and Market. Mohamed is Abdiziz’s uncle. He is also owner of MZ Market LLC, which prosecutors allege was a shell company used to launder the stolen money. Mohamed allegedly pocketed $2.2 million. He previously pleaded guilty to passport fraud.

- Abdimajid Nur allegedly created a shell company, Nur Consulting, and laundered stolen money from Empire Cuisine and ThinkTechAct, other alleged shell companies. Abdimajid, who was 21 at the time of his indictment, allegedly pocketed $900,000.

- Hayat Nur allegedly submitted fake meal counts and invoices served at food sites. Court documents identify Hayat as Abdimajid’s sister. Hayat allegedly pocketed $30,000.

- Said Farah co-owned Bushra Wholesalers, which allegedly laundered money by claiming to be a food vendor that provided meals to food sites that then reportedly served children. Court documents identify Said as Abdiaziz’s brother. Said allegedly pocketed more than $1 million.

- Abdiwahab Aftin co-owned Bushra Wholesalers, and allegedly pocketed $435,000.

- Mukhtar Shariff served as CEO of Afrique Hospitality Group, and allegedly used the company to launder stolen money. He allegedly pocketed more than $1.3 million.